One of the first works to greet visitors to “Lawrence Philp’s Color Grid” art exhibit (through Sept. 11) at University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC) is “The Death of Picasso.” At first blush, the picture—which Philp painted in 1973, the year Pablo Picasso died at 91—does not appear to be a memorial, let alone a celebration, of the famous Spanish painter, known in part for pioneering the Cubism art movement.

An airplane flies through a pink-and-blue sky, as blue, orange, pink, yellow and other pastel-colored forms mingle below. On the right, a high-rise building defies perspective by tapering at the bottom and fanning out on the top. The more one engages with the picture, however, the more one notices—a common theme with the Georgia painter’s artworks.

“Expulsion from the Garden”

There is some sense of Cubism’s fractured forms in the picture, while a pair of yellow horns on the bottom recalls bulls and bullfighters, symbols of Spain that frequently appear in Picasso’s work. Philp offers an unfolding story that reveals increasingly more of itself to viewers who take the time to truly look.

Philp said irony and private jokes punctuate his homage to Picasso, an artist he greatly admires. “I really couldn’t do anything like he did, so I made that painting instead. It’s sort of like a kamikaze plane being aimed at the Tower of Pisa,” he explained.

Philp added that he didn’t want to make another “Picasso piece by Lawrence Philp instead of a Picasso piece by Picasso.”

To talk on the phone with Philp for an hour is to hear an array of references spanning the Middle Ages and Renaissance to the present day, stretching geographically from Europe to Africa to the far East, all marked by the artist’s wide and deep reading. Philp—who was born in 1949 and has lived in New York, Rhode Island and Michigan—also dispatches a host of inventive metaphors. Finishing one work and moving to another, for example, is “like jumping off a horse and then jumping back on.”

Philp start his works by scribbling on paper—the “automatic drawing” he says is beyond his control. A paper full of scribbled marks gives him something to which he can respond. He might cover the bottom layer, what he calls “making a surface that is relevant to itself,” with Cray-pas oil pastels or with watercolor. He also draws, erases, draws over and collages to build up his surfaces.

“It’s like a crazy quilt kind of thing,” he said. “I’m not trying to render a figure in space. I’m trying to kind-of render the space.”

He titles his works with a range of names, several of them religious. “Expulsion from the Garden” (c. 1972-73) evokes the Genesis story of Adam and Eve. “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” (c. 1973), meanwhile, offers just one hint of its religious theme: a red cross near the center of the composition. This mostly red and orange picture is largely abstract, evoking a desert bisected by a thin river. Some sort of structure occupies the top part of the picture and a fire hydrant, telephone and gasoline pump fill the foreground and middle ground.

“Golf Course of Life”

Knowing the title, the notion that communications technology and car fuel could tempt someone committed to introspection and religious prayer will ring true to any parent who has asked a child to put away a phone at the dinner table or to anyone who has tried to have a conversation with a friend or work colleague who is checking email.

Philp reveals that he grew up in the church but left after reading conflicting things about Christianity, particularly references to corrupt popes in centuries past. He is more at home in African religions and in Buddhism; he practices a form of the latter called Nichiren Shōshū, which involves chanting the mantra “Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo.”

Philp doesn’t consciously connect his religious practice to his art-making, though, and the religious-titled works in the show were inspired by medieval Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch and Italian Renaissance artist Masaccio.

When Eric Key, director of UMGC’s arts program, traveled last year to Philp’s studio 40 miles southeast of Atlanta to select the works for the exhibit, he said he noticed certain symbolism in the artist’s work against. Key asked Philp about the layers, grids and textual inscriptions in the work, which seemed to offer social commentary at times. The artist said that was not his intent.

“But that’s exactly what it is,” Key said. “When you talk to him, you think there is no message in the work. He gets into this zone where he just creates.”

Philp’s titles pregnant with social meaning include “Golf Course of Life” (c. 1972), “Upstate Aggression” (c. 1995) and “U.S. Dollar” (1999-2000). The latter, part of his Leaving Home Series, is a mixed media work on paper that contains a lot of text. The phrase “U.S. Dollar” appears on a green rectangle at the top, beneath which three syringe needles press into an arm and the words “New Jack Slavery” appear. Inscriptions appear elsewhere in the composition—“U.S. Yen Pound” and “One Money”—and one can discern letters and numbers and phallic shapes. Other texts are murkier.

Key was moved by the connection between money and drugs, and he figures there is a message in Philp’s work. But he said Philp is the kind of artist who seeks to hole up in the studio and

buttress himself against what is happening outside—whether social or political—rather than the sort who mines current events and responds to them.

“He believes in building things up to find out how or if they work for what he wants to create as a finished work of art,” Key wrote in the catalog for the UMGC exhibit. “He enjoys working with his hands; he has done so all his life.”

Beyond making art, Philp has been a handyman, contractor, house painter and drywall installer, all of which informed his art, according to Key.

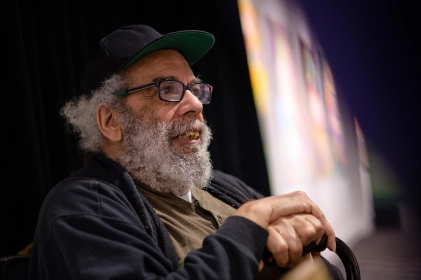

Lawrence Philp

In Key’s view, Philp sees himself as somewhat removed from society, including the race riots in Detroit where he lived at the time. Philp told him he wanted to escape that in the studio, rather than engage it in his art.

“My follow-up question to him was, ‘Did any of that experience show up in your artwork?’ His answer was, ‘No,’” Key said. “To me it’s a direct parallel to the dollar and to what the dollar is doing with drugs.

“You can get energy from it that can be very relevant to what’s going on today in terms of drugs, politics, social statements and chaos,” Key added.

Philp said he does follow current events and the news on television and radio, but he has to shut those down when they become too much for him.

Untitled work by Lawrence Philp

“I think that if you want to work on something seriously, a lot of the stuff that is happening around you takes your attention away rather than necessarily helping you apply your attention,” Philp explained. “All the things that have been going on in my life about race or politics or something like that has been going on for years. It’s almost like a dull repetition after a period of time.”

One can either rail against that or, as he chooses, just work. Philp said he would much rather make art than to go into the street and fight because many of those he knew who did the latter did not live long.

One common element in Philp’s work—the preponderance of bananas—builds on a different side of him, his playful nature. He also connects the fruit to his heritage, hinting at both the elaborate edible headdresses that Carmen Miranda wore in movies and to the bananas, yams and pineapples that are endemic to Jamaica, where his parents grew up.

“I always put them in the painting. Those are sometimes the first marks that I start with,” he said. “In the automatic drawing that I do, I always find these elongated figures that later on look like bananas.”

A few minutes later, he added: “You might even think about banana republics.”