Andrew Eyerly is the outreach director for the Citizens Climate Lobby, an international grassroots nonprofit with more than 200,000 supporters. How the Army veteran got there is the story of a University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC) professor who saw Eyerly’s potential and offered help at each step of his career.

Like many UMGC students, Eyerly—who goes by the first name Drew—joined the Army right out of high school. He came from a small Pennsylvania town and was only the second in his family to graduate from high school. No one talked about college.

“There was nobody really to help me with that process, and at 17 years old, it was just overwhelming to me,” he said. “It was just easier for me to sign on the line, put on a uniform and go off and do that stuff.”

The Army was good to Eyerly. During the first two years of his service, he became a preventive medicine specialist trained in environmental and occupational health. His job was to limit soldiers’ exposure to hazards in their environment. He saw the effect on soldiers’ respiratory systems when that didn’t happen. After seven years in the service, he became a combat medic.

During his tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, he found himself increasingly focused on how fuel convoys were linked to servicemember casualties. He could see that petroleum is needed in every aspect of overseas military operations. That sparked his interest in how a more sustainable U.S. energy infrastructure could lessen dependence on other countries.

As he expanded his understanding of the energy infrastructure, Eyerly was also deepening his conservative political views and questioning the role of government regulation and taxation. He wasn’t worried about climate change. He saw it as a problem for the far future that did not affect him.

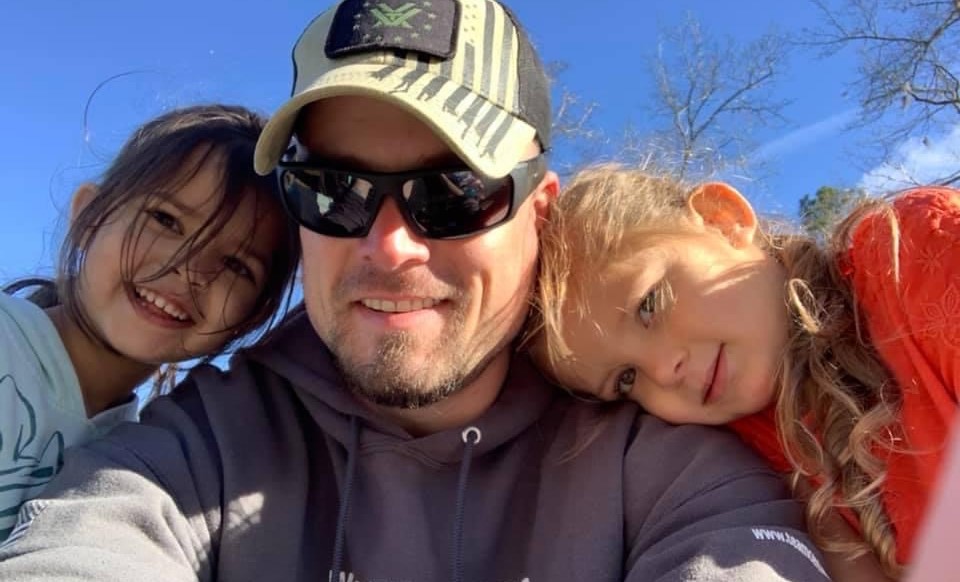

Until his daughter was born.

“It took the birth of a 10-pound baby girl—with cheeks so big, she couldn’t open her eyes—to get me to open my eyes,” he said.

Leaving the Army, Eyerly wanted to continue his education. One college told him he would have to start from scratch to earn credits for graduation. Then he found UMGC and its environmental management degree. He enrolled after a counselor informed him that his military training would translate into 45 to 55 credits, shaving about a year and a half off the time it typically took to earn a bachelor’s degree.

As part of his program, Eyerly ended up in the virtual classroom of Professor Sabrina Fu, who now directs UMGC’s Environmental Science and Management Program. Fu noticed that Eyerly was not active in discussions in her classes. She didn’t realize he was biting his tongue because he believed his classmates did not share his political philosophy regarding government regulation and taxation. She encouraged him to speak up, and he took her advice to heart.

“Everyone was just tax, tax, tax,” he said. “I guess I lost my cool a little bit. I put my real thoughts all over the discussion board.”

A day or so later, Fu sent him an email. Eyerly replied with an apology for his rants in class, but his professor encouraged him to speak out, telling him that conservative voices were needed in the climate change arena. Fu was working with Citizens Climate Lobby (CCL), which trains volunteers to build relationships with elected representatives to influence climate policy. The organization supports carbon fee-and-dividend legislation through which carbon fees would be collected and returned to taxpayers as direct payments.

Fu invited Eyerly to check out the organization’s website and arranged a scholarship so he could attend his first “lobby day” in Washington. He found he could talk with ease to people there about his conservative ideas on how to fight climate change—something he could not do in his conservative social circle in Evans, Georgia.

He said CCL “helped me with my advocacy and how to speak on this topic without being adversarial.”

As soon as he completed his B.S. degree in Environmental Management at UMGC, Eyerly immediately enrolled in a second bachelor’s degree program—in occupational health and safety—at another university while working with the Environmental Protection Division in the George Department of Natural Resources taking air samples.

That’s when Fu contacted him again. Citizens Climate Lobby was looking for someone to head its outreach to conservatives. She thought he would be a perfect fit. Was he interested?

Fu said consensus on climate change requires taking the case beyond a one-sided viewpoint, something she believed Eyerly capable of. When the lobby’s president asked if she would recommend Eyerly, Fu was quick to endorse her former student.

“All I know is we can’t keep doing things the way we have been doing it,” she said. “Drew comes from a very different background than most CCL members, and he offers a perspective not often heard there.”

Because of his military service and background, he is able to talk to staunch Republicans, she said. Since he’s only 33, he brings a youthful perspective. She noted that Eyerly has done a lot with veterans and with habitat conservation. She told the CCL president that he was just what the organization needed.

“I never thought in a million years I would get that job,” Eyerly said. “But [Fu] always had better ideas for me than I did, and here I am.”

Many conservatives oppose what they view as overburdening environmental regulation. A large percentage even doubt that climate change is a man-made existential threat. How does Eyerly open their minds?

“I begin by listening,” he said. “I find out where they’re at.”

He said many conservatives like him enjoy outdoor activities and hunting. He starts by noting the changes in their surroundings caused by pollution and climate shifts. “As a sportsman, you get to see firsthand how it’s impacting your lifestyle,” he said. “But a lot of people don’t make that connection.”

He also talks about the economic impact caused by pollution and its damage to the environment. He points out that those costs have to be borne by someone. Then he refers to conservative economists and the lens they use to evaluate the costs of climate change. Many of those economists argue that raising the carbon fee can strengthen the nation’s economy, reduce regulation, help working-class Americans, shrink the size of government and promote national security.

Eyerly said a carbon fee can generate three jobs for every one the fossil fuel industry creates without it. Still, he acknowledged, it can be difficult to bring conservative legislators onboard when their supporter base is suspicious of anything that addresses climate change.

“They need cover,” he said. “They need something that they can move behind while addressing the issue without saying that they’re addressing this issue. There are a lot of Republicans that are active in the discussion up on … [Capitol] Hill.”

Not only does Eyerly credit his UMGC professor for guiding him to his job with Citizens Climate Lobby, but he said Fu’s influence on his career continues.

“She doesn’t take no for an answer,” he said. “She is so passionate, she’s so energetic about things. You can’t help but fall in line with her perspective. It doesn’t matter if you are uncomfortable with the topic or not. You’re going to address it because you want to work with her. “She’s someone I know I can call and talk to and get honest feedback.”