UMGC Arts Program Shifts Gears During the Pandemic

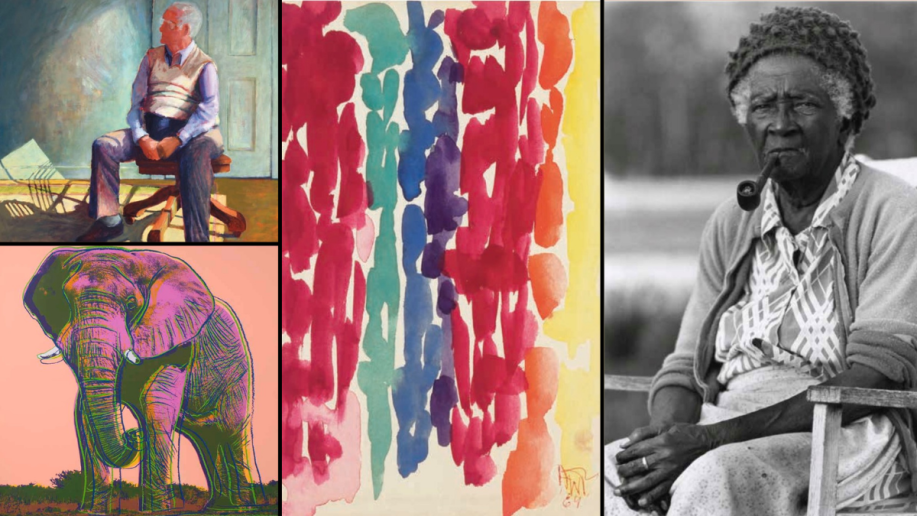

In a darkened room, a white-haired man in a sleeveless, striped sweater sits on a wooden swivel chair before a door. The title of Sharon Wolpoff’s 1988 oil painting, “Waiting for the Electrician,” explains the scene. Yet the work is much more. It is a symphony of abstract forms where, in this instance, the shadow cast by the chair alternatively evokes fossilized dinosaur bones, a stringed instrument such as a harp, and a gridded Piet Mondrian painting.

With a year of social distancing, pandemic, and relative isolation behind us, the work of Wolpoff—a Washington, D.C.-born artist—feels like it is channeling the quarantine. A unseen electrician is evidently en route, but anything, say even a global pandemic grinding the world to a near standstill, could happen. Perhaps the man in the sweater awaits Godot, to evoke Samuel Beckett’s famous play about pining in vain for an arrival.

The painting is a gift by the artist to the University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC) Maryland Artist Collection. It is also one of 10 artworks that UMGC has printed and mailed to supporters of its Arts Program as part of the Stay Connected initiative during the COVID-19 shutdown. According to printed materials, the Arts Program “will renew its exhibition program upon the reopening of site operations” and all previously slated exhibitions, including a survey of Wolpoff’s art, will be mounted when it is safe to do so.

In the Stay Connected mailings, each printed work from the UMGC collection is sized for framing, said Eric Key, director of the Arts Program, and accompanied by information about the artist and the art. In the case of Wolpoff’s painting, “it is at the moment when the light appears that artistic creativity strikes. She sees more than just a well-lit space; she sees how the space is transformed.”

Wolpoff also explores the ways light affects color. “For example, what at first appears to be a navy blue might become a lighter blue or sky blue with a ray of light on the surface,” according to the notes about the painting. “This play of light on color inspires her to discover how different shades of one color can change the tenor of a work. It is this union of color and shapes, this fusion, that she demonstrates in her work.”

Nine other printed works from UMGC’s collection scheduled to be mailed over the next few months are: a circa 206 B.C.E. to 220 C.E. cauldron—perhaps part of funerary set—by an unknown Chinese artist; Selma Oppenheimer’s 1960 painting “Girl in Yellow Hat;” an untitled Alma Thomas 1969 watercolor painting; Paul Reed’s 1971 acrylic painting on paper, “Gilport One,” from a series called Gilport; a silver gelatin print of William Anderson’s 1978 photo “Woman with Pipe;” McArthur Binion’s circa 1978-79 crayon-on-aluminum work “152 W. 25th Street;” Nelson Stevens’ 1983 mixed media work “Stevie Wonder;” Andy Warhol’s 1983 screen print “African Elephant” from his Endangered Species series; and Curlee Raven Holton’s 2017 oil painting titled “Dream Bait.”

The notes accompanying the images are rich with detail. Among other things, recipients are informed that Warhol was born Andrew Warhola and that a movement called AfriCOBRA stands for “the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists.” Photographer Anderson, who was born in Selma, Alabama, in 1932, said of his artistic approach, “I believe there is beauty in all life … I look for people whose faces tell a story.” Anderson died in 2019.

Biographical information offered through the Stay Connected initiative points out that Thomas’ career was marked by several historic firsts. She had her first solo exhibition at age 68 and was the first African American woman with a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She was also the first African American woman whose work was acquired by the permanent collection of the White House Historical Association and displayed at the White House.

When Key closed UMGC’s art galleries on March 15, 2020, he thought it would be a short-term measure. As it became clear that the pandemic would necessitate longer closures, he had to take measures to reschedule exhibitions.

“We were curating our own shows, so it was easier for us to communicate with artists and owners and let them know what was going on,” he said. “As much as we would have liked to stay on schedule, of course they all understood.

”We were very clear that we were not canceling. We were postponing,” he said.

After polling community members, Key decided that printed materials, rather than virtual artist talks, were the best way to stay connected for now.

“Our arts patrons were really getting burned out with those meetings, and they didn’t really feel a connection to the artwork. We decided not to do Zoom meetings,” he explained. “We decided to do print media instead.”

Stay Connected is the reminder to the UMGC community that the Arts Program is not closed for good. In showcasing many past exhibitions, artists' talks and works from the UMGC collection, it also shows the breadth of the 35-year-old program.

“We also wanted the public to stay tuned—kind of like a teaser—to see the works up front and close when the program reopens,” Key explained.

The Arts Program had just completed the 4th Biennial Maryland Regional Juried Art Exhibition on March 1, 2020, when COVID-19 restrictions began. The facilities department and the security team ensured the safety of the juried artworks, displayed in the program’s rotating gallery, until they could be returned to the artists. Key said he was able to go in for a day or two to take the works down. Artists came to the building’s loading dock and retrieved their pieces,

“If the building is on lockdown, it’s on lockdown. You can’t get in nor out,” Key said.

The permanent collection remains hanging on the gallery walls. Conservators are not present in person but the collection has been safeguarded by 24-hour security during the pandemic.

Exhibitions are not the only thing disrupted by COVID-19. The pandemic also affected plans for a return art trip to Cuba for the Cuban Biennale. A 2019 trip generated enough interest that the 2020 trip was on track to sell out before the pandemic hit.

Key said he looks forward to when he can resume planning arts education trips.

With the pandemic, Key and the Arts Program directors had to pivot their focus. They have been hard at work on the longer-term project of digitizing the university’s nearly 3,000 works of art. That has meant planning photo shoots of some works and finding existing professional shots of others then uploading images into collection software while ensuring that the text describing each work is accurate.

With help from IT technicians, Key and his colleagues have been learning new computer software programs. When the building reopens, they will confirm the sizes, media, and key characteristics they must know in order to virtually present the works—and their artists—to the general public.

Until then, Key recommended that people who are exploring art online pay attention to the virtual events produced by the Smithsonian Institution, local Maryland galleries, and David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at University of Maryland. He said Driscoll’s legacy, in particular, stands out for him.

He also encouraged art lovers to hang onto emails about exhibitions. “Keep them as a reference. Then go to the institutions to see the actual works when those organizations reopen,” he said. “Seeing the emails will only pique your interest in seeing the work in person.”

Key said virtual exhibitions where viewers click on arrows that help them “walk” through galleries have not provided him with the closeness to art he seeks. He tried a virtual walk-through with Hauser & Wirth gallery’s Amy Sherald exhibit. Sherald famously painted former first lady Michelle Obama for the National Portrait Gallery.

“I was more interested to get to the pieces so I could see them, but even looking at a piece, I felt a distance from it. I didn’t feel a closeness to it,” Key said. “As much as I respect the intent of the gallery to show the work, I couldn’t see the brushstrokes. I couldn’t see the details that I would look at in person.”

It is impossible for Key to predict when the UMGC galleries will reopen. Once the university deems it safe to do so, the Arts Program will begin planning its postponed exhibition as well as future shows and programs.

“Personally, and as the director of the program, I was obviously very disappointed that people didn’t have access to the art,” Key said. People who frequent art galleries, including members of the UMGC arts community, have told Key they missed that access.

Even people who are not regular gallery visitors said they missed having contact with art.

“On a larger scale, we take art for granted, but it really does serve a higher meaning and a higher calling in the community,” Key said. “We’ve always known that art had its place. This just validates that it does.”